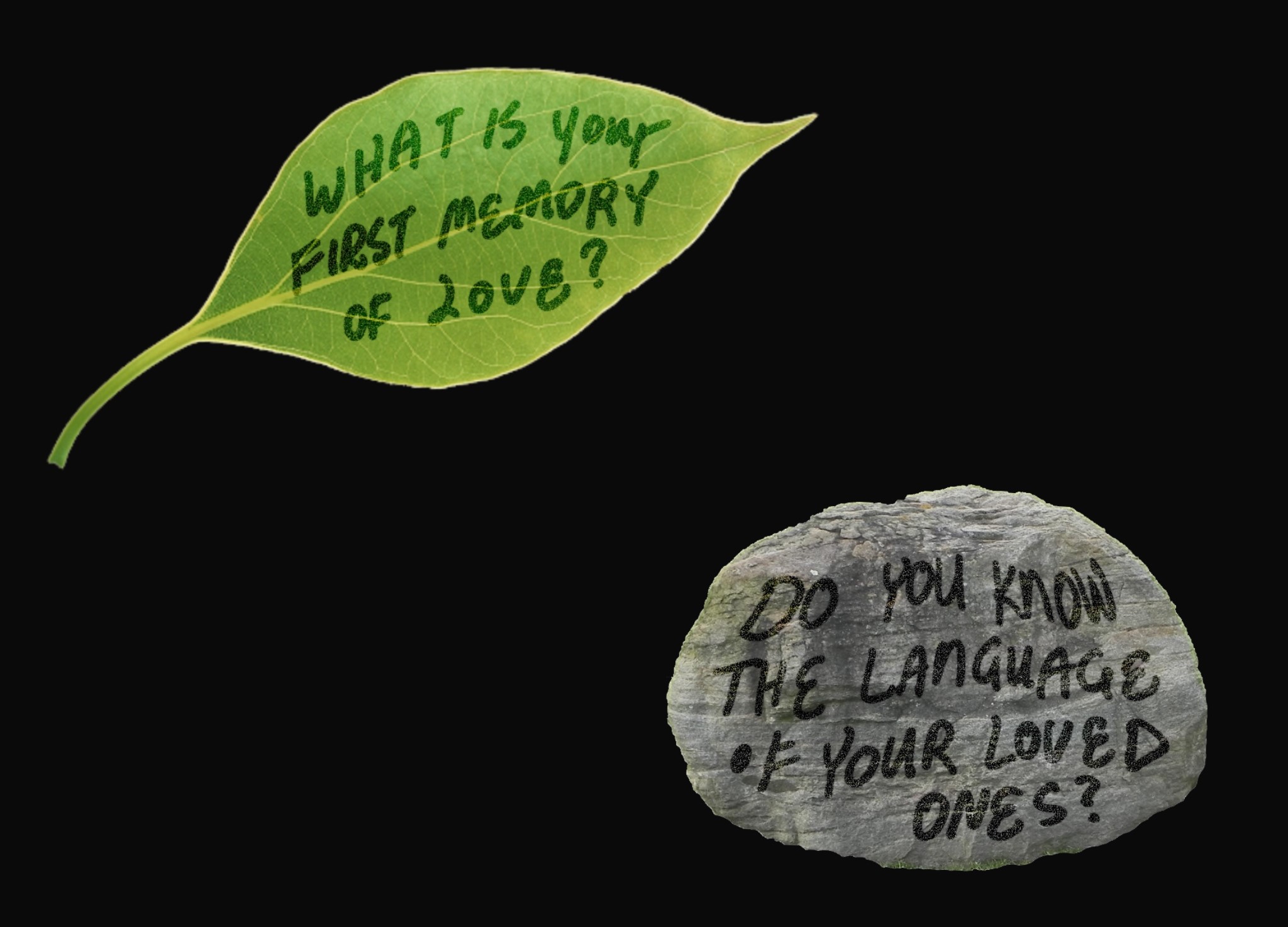

This project was borne out of two questions:

“What is your first memory of love?” and

“Do you know the language of your loved ones?”.

For my family, our memories of love are stored in the bits of voice messages on WhatsApp/WeChat, aged photographs of my parent’s hometowns stashed in cloud storage, and history logs of conversations with loved ones on Google Translate. Like us, digital technology holds memory and becomes a medium for communication while also revealing a distance in connection. For Asian diaspora there is a common experience of a loss of language and tools to communicate with family–and by extension, a sense of ungrounded roots and liminal belonging. My project explores the transformative power of reconnecting to the wisdom of our ancestors and the uniqueness of our personal histories within. It honors the presence of the past, as much as a recognition that we are also future ancestors ourselves.

I knew I wanted my project to be something woven from these ideas: language or lack of it, technology for remembering & preserving, roots, trauma & the body, immigration, and song & poetry.

My first ideations were speculations on technologies that could aid in processing trauma in the body differently,

1) sensory suit that could somatically transport people to a pleasant memory

2) cognitive editing for our brain systems in charge of stress/fear

3) tears that could be used as a salve for healing others

I wanted to address a more humanistic look at trauma and felt that my ideas came at it from a more clinical problem-solution view.

My project shifted as I was motivated, instead, by poetry, song, and the senses. This shift was inspired particularly by Octavia Butler’s short story “Speech Sounds” which envisions a world devastated by a pandemic that has left people unable to speak, understand words, or read, exploring how people depend on each other to survive.

My focus then turned to language and the wound of being misunderstood, which reminded me of a poem my friend wrote that starts with: “do you know the language of your loved ones?” (Kelin Sophia Tham, confessions line 1). When confronted with that question, my initial answer was—no, I do not know the language of my loved ones. I felt that I had lost the language of fluently talking to my parents with many of our conversations mediated through Google Translate, and using technology to speak for me– and all of the inaccuracies, conflicts, misunderstandings that come from translation.

I felt that not only had I lost my cultural language, but also language of recognition, and the language of belonging.I wrote a poem in response, with a snippet that goes: “Language as possible to speak! / Language as possible to speak against itself

/ Do you know the language of your 爱的人?(No) / 心—不知道—要什么 / 你为什么离开?/ Language not enough / Language not enough of what / What language is enough? / What is enough’s language? / Enough of language / Language of enough /”

The first two lines was about English as giving me the ability to express but also evidence of what it replaced, what went missing, what is lost; I’m possible to speak because of English but I can also speak against English.

bell hooks writes about the ties between language, conquest, and domination when reflecting on Adrienne Rich’s poem “The Burning of Paper Instead of Children”. She states: “in the United States, [standard English] is the mask which hides the loss of so many tongues, all those sounds of diverse, native communities we will never hear”.

The Chinese characters in my poem say: “Do you know the language of your loved ones? (No) / Heart – does not know – what it wants / Why did you break away?”

I wrote in Mandarin, the official language of China, despite my family speaking Cantonese (spoken by certain Chinese provinces). My mother speaks Toisanese, a Cantonese dialect, and particularly a variation of Toisanese that is specific to the village she is from; her native language is mainly oral with no standardized way of writing.

I felt this disconnection in language and by extension, a loss in belonging, as an estrangement from a memory of love.—something felt missing, lost, and not enough.

In this process of immigration, how do we access what’s lost? Like language, sense of belonging, nostalgic memories, feeling of home— I desired to preserve what felt lost in the rust of the past.My early inspirations in the research process were works that sought to document history, very much rooted in the passage of time:'

1) Photojournalist Alan Chin in “A Home 8,000 Miles Away” photographed his ancestral home and writes about a “forgotten rural China, engulfed in a crisis that is quiet but sustained”.

2) Artist Ethel Tawe in “Image Frequency Modulation” dug into her family archive, layering analog photos, digital videos, and proverbs in her mother tongue exploring “ancestral memory, transmission, oral tradition, and metaphors of radio tech as sites of possibility for the African diaspora”.

In thinking of documentation, I tried to find my mom’s village on Google Maps and wasn’t able to.. dislocated somewhere in the computer-generated ridges of mountains and shrubbery of Guangdong. There are also no photos from their time growing up in their village—somewhere displaced.

Writer Neema Githere says,” Diaspora is the wound that is full of possibility. This feeling of dislocation and displacement necessitates the formation of new narratives and hybridization.” This quote quite honestly brought me to tears. It also became the central moving inspiration behind my project development:

My early speculative ideations after focused on the Wounds part of Githere’s quote, centering displacement and grief and shame and regret. The wound of hearing my mom’s stories, a lot of her talking about the suffering she faced in comparison to the life we live now in America, shame about our origins, about the past, and the idea of looking forward and never turning back! I thought! What if objects could speak their history? And preserve this past I did not have direct access to, that I felt was important and desperately needed to be remembered.

The poster shows a bag of lychee, with the pronunciation in romanized Cantonese underneath it, and the lychee is saying: “he sold her education for me to feed his hungry heart”. The history this bag of lychee is speaking, is a memory my mom recalled while laughing a strange laugh—she tells me about how her dad had used the last of her tuition money to buy a bag of lychee. When we think of tuition here, we think ‘college’, but for her it was the third grade.

Despite visiting my mom’s hometown in 2008 and 2012 and taking this family picture, (what is now the only remaining family picture on my mom’s side) I do not have any memories of my grandparents. I just remembered being very mean to them, a result of obvious cultural and generational differences and underneath it, my desperate attempt at fitting into America, the blunting process of assimilation. One way I did that was by rejecting that part of my culture, that part of me. Seeing what America had “othered” and doing the same.

A decade later I feel myself grasping for what was lost in that process of rejection and assimilation. There are strong feelings of regret for the ways things could have been different, every alternative present. Going back to that memory of love and inquiring on how we access what’s lost, I wondered: Is it even lost at all?

Circularing back to Githere’s quote about possibility in new narratives, I realized there was wisdom in this less developed memory—because it wasn’t

all suffering..in fact, in some ways, people were happier. Despite having no electricity, no running water, no technology the way we typically know dominant technology, as well as leg-sucking leeches and spider hunts and running around barefoot…there was also this precious innocence—a vibrancy and carefree-ness that feels very special to that place. Here there are dedicated parks where we go and kids with their families play, but in the village, the entire environment was a place of play and also a place where using the resources they had, they invented creative ways and strategies of living that was collective and non-wasteful.

Obviously there was a lot of stuff that wasn’t good, not trying to totally romanticize this past but there is this tendency to represent under-developed places and the people in those places as pitiful, poor, and these starving kids people needed to go and save them, especially that ‘savior’ part. So this possibility of a new narrative, that that’s not the entire story, and reclaiming agency in that. That there were moments of joy. That there had already been long established traditions of people caring for each other and inventions of technology for survival.

I term my original speculative question: “what if objects could speak their history?” as the

static deficit model. The design problem I identified was an inability to speak and incapability of connecting and communicating, which led me to the design solution of

object as preservationist, preserving history that one feels like they can’t access.

I realized that from the get-go I had already framed the starting point of my project from a limiting belief, meaning that everything stemming from it would be bounded by lack. The design problem was a perceived character flaw, therefore, the design solution placed emphasis on disconnection; what can’t happen, what can’t be changed, what isn’t possible, what is an inevitable deficit of the individual.

My storyboard off of this model brings this fragmentation of the parent-child relationship to the surface, depicting senses that are disparate, distorted, and indiscernible.

My finalized question, instead: “What if we could hear our ancestors through our heirlooms?” frames the design problem as: it’s not that we’re incapable of communicating or connecting but we’re simply not given the tools to do so or the tools we had to do so were taken away or erased (so it’s merely a matter of finding it again). The design solution:

heirloom as mediator foregrounds reciprocity, emphasizes continuity, as well as listening and learning how to RE-connect. This question encourages expansion and growth rather than an investigation into the scar of incomprehension.

Returning to the final part of Githere’s quote, the wound full of possibility as hybridization—When imagining a particular heirloom, traditionally the dominant ideas of ‘heirlooms’ are like precious jewelry, fragile pottery, or family crests accumulated and protected over generations. Instead, I imagined heirlooms as natural things that withstood time through natural cycles of death and rebirth.

I imagined a conch that could connect the user to their ancestor, in this case, the heroine’s grandma.

The main heroine of the story is AGENT I.M.B. or Bimbi for short. In this world, the state has decided to sedate its citizens to prepare them for cyborgism—what they believe is the next stage of evolution for a more productive and efficient species. They use invasive technologies to dampen people’s senses and erase memory. Over time they begin to perceive the world through a distorted, hypnotic lens and their sense of sight degrades into black and white. Only through connecting to her grandmother via the conch and broader social networks, does Bimbi see, hear, taste, smell, and feel clearly and multidimensionally!

+HiveMind: mechanically altered bees with stingers that have been pumped with mind-altering chemicals, their rapid flapping of wings causes a disorienting buzzing, rendering people dizzy; they target people’s eardrums and when the person is stung, the person is programmed into the HiveMind network where they feel an insatiable desire to return to the HoneyQomb and consume honey

+HoneyQomb: physical headquarters of the HiveMind that is a human-sized honey comb comprised of artificial honey engineered to degrade memory for those connected to its network; Bimbi does not like sweets as she grew up eating bitter melon and bitter candy! it takes longer for the process to affect her; while eventually the honey takes effect on her memory/senses she sometimes catches glimpses of truth in her dreams and vision flashes

+Kaleidoscope: social magical network (powered by butterfly bandwidth), they form a protective shield around the person coated in honey. They then drink the nectar off, restoring the memory and senses

I looked at the phenomenon of extrasensory-perception, specifically, clairaudience: “having or claiming to have the power to hear sounds said to exist beyond the reach of ordinary experience or capacity” (Dictionary.com). While scientifically, ESP remains a controversial debate amongst researchers, with parapsychology (the study of psychic phenomena) facing critiques on replicability and experimental set-up, the concept of clairaudience has existed in cultural practices like Buddhism where it’s referred to as the

‘divine ear’, as well as the Victorian spiritualism movement of the 19th century with an emphasis on mediumship.

I also drew inspiration from the practice of Chinese ancestral worship from traditional Chinese folk religion (or ‘Shenism’ as coined by Western academics, from

bàishén: “worshipping the Gods” via incense, tea, fruit). Anthropologist Vivienne Wee describes Shenism as “an empty bowl, which can variously be filled with the contents of institutionalized religions such as Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, the Chinese syncretic religions".

In Shenism, there is a focus on kinship and belief that the deceased continue living, look after the family, and can influence fortune. There are

customs of giving food and incense offerings to ancestors and deities in respect and honor.In this imagined world, channels for sensing (sound, taste, sight, smell, feel) become the basis for understanding the language of the world and how one moves through it.

The sound element borrows from the idea that certain sound frequencies have an impact on brain-waves, with

meditative binaural beats theorized to help with stress-relief, sleep, and anxiety. On this principle, sound frequencies can also be intentionally manipulated to control or influence behavior. In my speculation, there are different networks (both electronic and social relationship networks) that utilize sound to either disrupt or open up communication and connection.

There is the HiveMind (cyborg Zombees), the Blu-Trooth (ESP conch allowing for transtemporal communication), and the Kaleidoscope (butterflight bandwidth), combining natural elements (bees, conches, and butterflies) with either mechanical or magical components, or a hybrid of both.

The present is the past and the future colliding. One’s feelings and understandings about the past can form a trajectory for the future, that can either feel static and liminal or dynamic and fluid. This project is an homage to the legacy of immense love that it took to be here as an individual, and also as a larger collective, with each other at this particular moment in time. The idea that the past, present and future aren’t mutually exclusive can be connective tissue to a greater, grander memory of love and a gift of greater clarity to what belonging truly means.